Trends in Market Efficiency

If you believe markets are efficient, then there should be limited predictability in stock returns. Why? Suppose returns were predictable: specifically suppose you received some information that the returns of Apple (AAPL) were certain to be high in the future. On this information, you start buying AAPL today, which pushes up the price, and pushes down future returns. Now, suppose it’s not just you who received that information, but all investors – and this is likely true, as long as you are not doing insider trading! Then everyone will demand AAPL and push up the price even more today, further pushing down future returns. If all investors can trade on this information instantaneously, the price would instantaneously adjust to the good news, and your information would have no predictive power for future stock returns.

In the data, however, return predictability has been well documented (see e.g. Discount Rates by John Cochrane), but this predictive power only exists over longer horizons, and is usually attributed to time-variation in risk premia. An example of this would be that at the bottom of a recession, predicted future returns i.e. risk premia are high – there is a lot of uncertainty about the future path of the economy, so investing in stocks is perceived as risky, and investors must be compensated accordingly – further, not many investors have capital to put into the stock market, so even though expected returns are high, prices stay low and predictability remains.

In this post, I am going to show how predictability over shorter horizons – of one month to two minutes – has changed over the past 100 years.

Set Up

One way to measure return predictability would be with a regression like: \begin{equation} r_{(t+n,t+1)}=a_n + \beta_{n}r_{(t,t-n-1)} + e_{n,t} \end{equation} where \(r_{(t+n,t+1)}\) is the cumulative return from \(t+1\) to \(t+n\), and \(r_{(t,t-n-1)}\) is the cumulative return from \(t-n-1\) to \(t\). Suppose \(n=5\) trading days: then this regression is using last week’s return to predict this week’s return. If predictability is high, we would expect \(\beta_n\) to be large in absolute value, and the R-squared i.e. the percent of future returns explained by past returns to be high.

I am going to run this regression with two sets of data: One is going to be ‘low frequency’, built up from daily returns on the CRSP value-weighted index from 1927-2018: the horizons will be 1 day, 5-day (one week) and 22-day (one month). I am also going to use high frequency data on S&P 500 futures, and look at predictability over shorter intervals: hourly, 30-min, 15-min, 10-min, 5-min and 2-min. The high-frequency data I have runs from 1983-2015.

Results

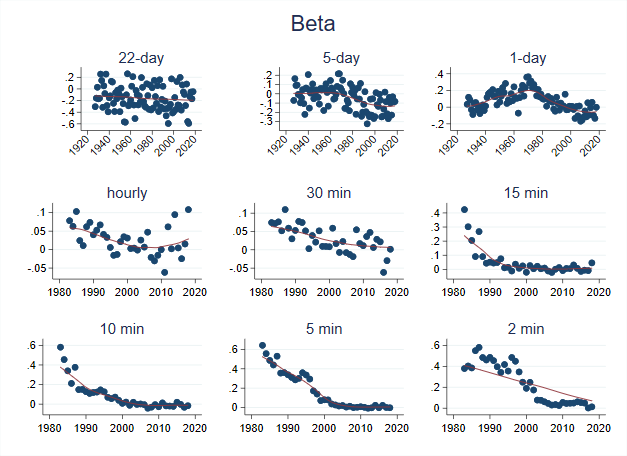

I run the regression described above at each horizon, every year (i.e. using one year of data at a time), and plot the \(\beta_n\)’s for each year in the figure below:

In all the plots, the red line represents a moving-average of the betas computed each year. A blue dot near zero would imply predictability is low in that year.

For the 22-day and 5-day frequencies, there is a weak downward trend over the past 100 years. For the 1-day frequency, it seems like predictability increases from the late 20’s to the 70’s. An explanation for this is that the Great Depression was a period of extreme stock volatility (check out the data my co-authors and I posted at: https://stockmarketjumps.com/), so short-run predictability had to be low. As we came of of the depression, and volatility declined, predictability mechanically increased. Later, as markets became more efficient, the 1-day predictability decreased.

The high-frequency pictures tell the same story, but in a more striking way. If we look at the 15-min returns regression, it looks like predictability disappeared in early 1990’s. For the 10-min, it looks like it disappeared in the late 1990’s. For the 5-min, it looks to be the mid 2000’s and for the 2-min it is around 2010.

This is consistent with the idea that the market has become ‘faster’ over time. The massive improvement in technology, co-location of computers near exchanges, and the growth of algorithmic trading firms likely together eliminated predictability, even at very short horizons. As the market has become faster and faster, predictability at shorter and shorter horizons has vanished.

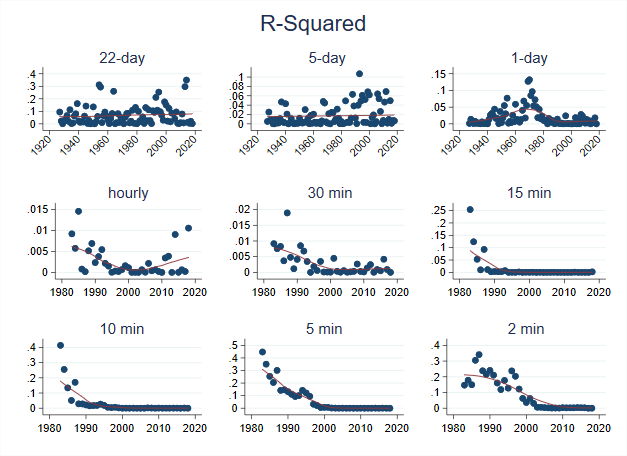

From the same regressions, I plot the R-squared i.e. the percent of variation in future returns, \(r_{(t+n,t+1)}\), explained by past returns \(r_{(t,t-n-1)}\) each year:

An R-squared near zero means zero predictability. I think R-squared values tell an even stronger story than the betas: The R-squared values at each horizon went to zero faster than the betas did! Even at times where there was some predictability left, the low R-squared values imply it would hard to consistently make money trading on this predictability.

Wrap Up

Mean reversion at the 1-day horizon has decreased significantly from the 1970’s to today. At the high-frequency level, things appeared to have changed in stages. In the 1990’s there was still some predictability at 10-min intervals, but by the 2010’s all predictability at any horizon has essentially vanished. This suggests that markets have likely become more efficient over time, and the idea that prices should be martingales is more true now than ever before.